The Eurovision Song Contest 2010 stage in Oslo, Norway. Photo: Kjell Jøran Hansen (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

For its many fans, the Eurovision Song Contest has long been an annual ritual, with the television broadcast watched by hundreds of millions and the entries closely scrutinized and criticized—notably, these days, on social media and on Eurovision-focused YouTube channels. For others, it's a kitschy, over-long event that, after 65 years, has overstayed its welcome.

But love it or hate it, there's no doubt that Eurovision—and the reactions it evokes—provides a compelling lens through which to regard contemporary Europe, its politics, its self-image and its presumed values.

The Eurovision Song Contest was born in 1956 as an annual television show in which a handful of countries in Western Europe competed with songs in their own language. The contest is still organized by the European Broadcasting Union (EBU), an alliance of public service media outlets, and with this year's event marking the 64th edition, it’s one of the longest-running and most popular shows in television history.

The rules have evolved over time, but countries select representatives at national level, usually through competitions that are themselves widely followed events in their home countries. Entries must include some kind of vocal and must last at least 3 minutes, and winners are selected at each stage both by a jury and by votes from audiences in the participating countries, with the caveat that audience voters may not vote for their own country representative. The country whose representative wins the contest usually goes on to host the event the next year. For certain entrants, Eurovision was the springboard to international fame, notable cases being Swedish band ABBA, who won in 1974 with their song “Waterloo,” and Celine Dion, who represented Switzerland in the 1988 contest.

Starting with seven countries in 1956, the contest has expanded to include around 40 nations, depending on the year, including some, like Australia and Israel, which are not part of Europe. To accommodate the increasing number of entrants, a system of semifinals was introduced in 2004 and expanded in 2008.

A slow but welcome change in representation and diversity

In earlier years, entries showcased mostly homogenized images of their countries, and mainstream musical styles. But over time the contest has become less white, less heteronormative, and more musically adventurous, mirroring the growing recognition across much of Europe of gender and ethnic diversity. The first openly LGBTQI+ artists performed in the late 90s, with Paul Oscar representing Iceland in 1997, and Dana International representing Israel and winning the contest in 1998. A milestone was achieved in 2014 when Austria’s bearded, evening gown-clad drag artist Conchita Wurst won the competition.

Eurovision performers are now also more ethnically diverse. The first Asian performer at Eurovision was Indonesia-born Anneke Grönloh, who represented the Netherlands in 1964.

In 1966, another Dutch contestant of Surinamese origin,, Milly Scott, became the first black performer to compete. Since then, the contest has featured a number of non-white entrants. Dave Benton, a singer originally from Aruba who was part of the act representing Estonia, became the first black person to win the competition in 2001.

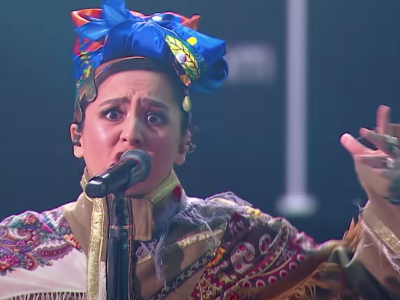

The 2021 edition of the contest features several black performers, representing countries such as the Netherlands, San Marino, the Czech Republic, Sweden and Israel. Austria’s representative Vincent Bueno is of Filipino descent, while Manizha, representing Russia, is of Tajik origin.

Musical styles have also changed over the history of Eurovision, going from romantic ballads in the 1950s to mainstream pop music in the 60s and 70s. Today, Eurovision songs run the gamut of popular music styles, from heavy metal to rap and electronic music.

The contest's geographic expansion has mirrored the gradual incorporation of the “other Europe” as the east-west Cold War division of the continent has shifted. The first significant change occurred in 1961, with the inclusion of Socialist Yugoslavia. Another expansion took place in the 70s and early 80s with the addition of Israel, Turkey and Morocco, and things accelerated after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when Eastern Europe and former Soviet states were included. The most recent addition to the list was Australia, which started competing in 2015.

An arena for airing out international relations

While Eurovision portrays itself as a cultural and entertainment event, as an international platform for showcasing a country’s identity it cannot escape politics.

While officially embraced by Eurovision organizers and performers, the issue of diversity remains a point of contention for national juries and audiences. A typical example is the case of Turkey, which joined Eurovision in 1975 and won in 2003. Turkey hosted the contest in 2004, but after 2012 withdrew from Eurovision altogether. Asked whether they would return, the head of Turkish Radio Television (TRT) said in 2018 that following Austrian drag artist Conchita Wurst’s victory in 2014, he could not possibly authorize the showing of such content on national television.

Similarly, there is reason to believe that Hungary, which joined the contest 1994, decided not to submit a song in 2020 because its government perceived the piece as being too LGBTQI+-oriented.

This year, the national jury’s decision to select singer Manizha, an outspoken Russian citizen of Tajik origin, to represent Russia was met with criticism and hate speech.

Real-life conflicts, whether armed or political, also play a substantial role in who gets selected to perform—or boycotted by national television stations and audiences in certain countries.

In 2009, Georgia, which joined the competition in 2007, entered a song called “We Don’t Wanna Put In,” a hardly subtle reference to Russian President Vladimir Putin, whose army had invaded parts of Georgia in 2008. The Eurovision organizers rejected the lyrics and asked for them to be changed. Georgia refused and withdrew from the competition.

In 2016, Ukraine, which has participated since 2003, entered a song called “1944” that retold the story of the deportation of ethnic Tatars by Soviet leader Stalin. The song was a clear reference to the 2014 annexation by Russia of Crimea. Russia tried to get the song banned but was unable to make its case and eventually withdrew from the competition that year.

Nor has the 2021 edition of Eurovision been free of politics. Belarus had its song rejected twice for being too political and ended up not participating in this year’s contest.

Another incident involved the North Macedonian contestant Vasil, whose video was filmed in a museum where one artwork, which appears only briefly, was perceived by some viewers as echoing the colors of the Bulgarian flag. This prompted a flood of comments, mostly on social media as to whether Vasil, who also holds Bulgarian citizenship, was making a political point.

A live event for pandemic times

Eurovision, like other live events, was also affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, which forced the contest to be cancelled in 2020 for the first time in its 65-year history. For the 2021 edition, drastic sanitary measures were imposed for the 39 contestants to be able to gather in Rotterdam for the contest in front of a limited audience. And with many nations in Europe and beyond still under various forms of lockdown, it’s anticipated that millions of television viewers—in 2019 the viewing audience numbered over 180 million—will be tuning in to the live broadcast of the final on May 22.

Read Global Voices stories about Eurovision

Stories about What Eurovision tells us about Europe

Slovenian rock stars Joker Out: From high school band to post-Eurovision success

Slovenian Eurovision sensation Joker Out discuss their creative process, touring and their upcoming album, which is going to feature songs in multiple languages.

WATCH/LISTEN: What Eurovision tells us about Europe

Missed the live stream of the May 20 Global Voices Insights webinar on the Eurovision Song Contest? Here's a replay.

LIVE on May 20: What Eurovision tells us about Europe

What does the Eurovision Song Contest say about the politics, self-image and values of Europe? Join us on May 20 to find out. Featuring interviews with two of this year's contestants!

Can the Eurovision Song Contest change Russia's views on migrants from Central Asia?

Russia has nominated Tajik-Russian singer Manizha as its representative for the 2021 Eurovision Song Contest. But many Russians reject her as the chosen face of their country at the international event.

Belarus banned from 2021 Eurovision contest for controversial song lyrics

The European Broadcasting Union found Belarus to be "in breach of the rules of the competition that ensure the Contest is not instrumentalized or brought into disrepute."

North Macedonia forced to re-edit Eurovision music video following nationalist rage

North Macedonia's nationalists have weighed a campaign against singer Vasil Garvanliev for "spreading Bulgarian propaganda" -- as two frames in the original video showed an artwork with the colors of the Bulgarian flag.

Afro-Czechs on visibility, racism and life in the Czech Republic (Part I)

The Czech society started discussing ethnic discrimination and diversity after the fall of Communism, which had erroneously claimed to have eradicated racism.

Russians Aren't Happy About Losing Eurovision, But They Weren't Happy Before, Either

Russia's narrow defeat this weekend in the 2016 Eurovision music contest wasn't the only tension in a competition full of lights, pyrotechnics, and nationalism.

Russians Hate Eurovision's Bearded-Lady Champion

On the Internet, Russians have reacted to Wurst’s victory with a mix of humor and homophobia.

Laughing at Russia's Eurovision Shooting Spirit

Earlier today, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov commented on his country's fifth place finish in this year's Eurovision Song Contest. At a press conference, Lavrov denounced supposed voting irregularities, claiming that Russia's points were "stolen," and called the anomaly "an outrageous act," promising Russian retaliation. Netizens were deeply amused.