Image by Rabin Pun Magar via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

This article by Rabin Pun Magar was originally published in Nepali Times, and an edited version has been republished on Global Voices as part of a content-sharing agreement.

The rugged mountains of Eastern Rukum district of Lumbini Province situated along the Dhaulagiri mountain range are all covered in late snow this winter. After a prolonged drought, it has finally snowed, but it is too late for the high altitude meadows to grow again. They have all dried up.

At 3,720m, visitors rarely make it to the high pasture at the mountainous Ma Kharka grazing region. But even until 20 years ago, every family in the village of Lukum brought its sheep and mountain goats for grazing up here. Shepherds with their flocks spent half a year in what used to be cool, green patches of grasslands. Very few do so now.

Rassa Gurung, 65, is one the last few shepherds carrying on their ancestral occupation. “I started coming here as a baby, slung over my mother’s back. We didn’t read and write back then, we all helped our parents tend the sheep,” he says.

Gurung knows every corner of this pasture like the back of his hand. His sheep used to graze freely, but now he has to watch that they do not wander into someone’s farm or enter the nearby community forest.

Rassa Gurung is one the last few shepherds carrying on their ancestral occupation. Image by Shristi Karki via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

The 8,167 metres tall Mt Dhaulagiri looms in the distance, and even the peak has little snow this year. It looks like a giant dark rock.

The sheep are also dying from mysterious causes. “Some 40–50 sheep die every year now. I myself have only 150 sheep now, down from 300 four years ago,” says Gurung. “Most of them die because they eat poisonous grass, as the edible grass does not grow in time. Some are eaten by leopards and bears.”

He adds: “It rains when it is not supposed to, and it does not snow when it is supposed to. Sometimes it does not snow till March, and other times it does not rain until June, so there is no grass to graze on.”

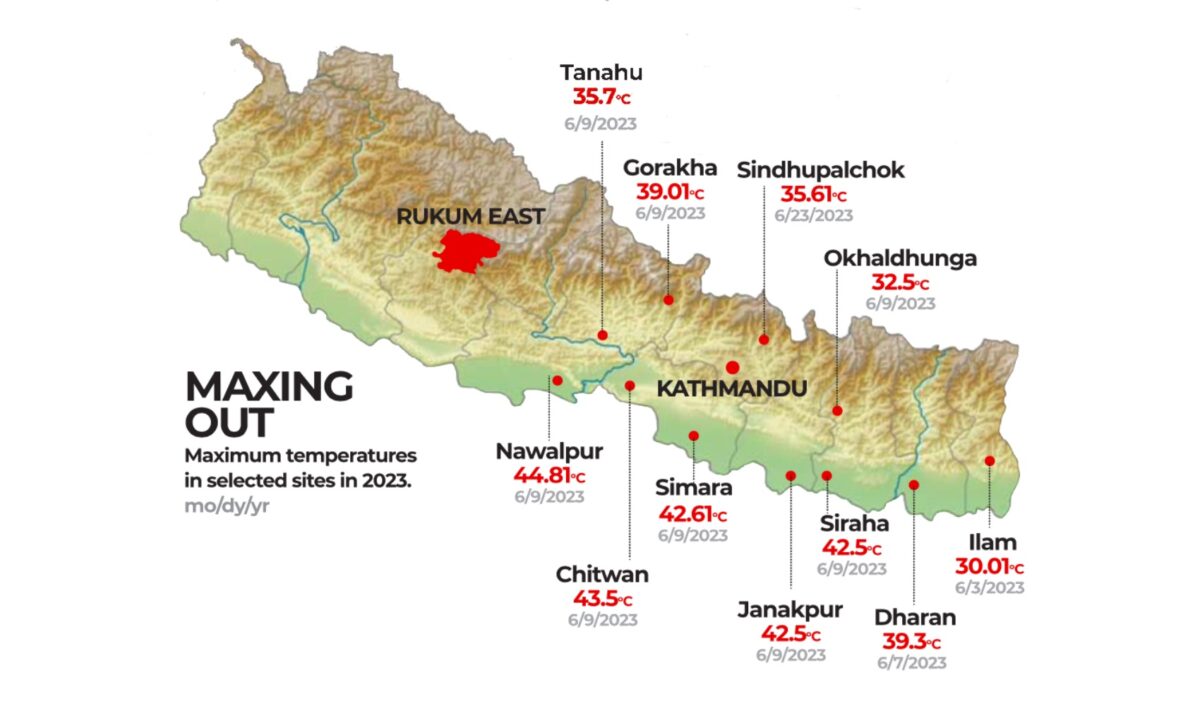

High-mountain communities are disproportionately affected by the climate crisis. 2023 was one of the hottest years Nepal has experienced.

“Farmers are affected directly by the increase in the average temperature. Unpredictable seasonal changes can lead to the growth of new species, and native Indigenous plants disappear,” explains climate scientist Ngamindra Dahal.

He adds: “Rainfall patterns have also changed. At times we have unseasonal cloudbursts, other times there is no winter rain and we get droughts. The absence of snow has affected sheep herders.”

Indeed, new kinds of grasses have started growing, and for shepherds like Gurung, there is no way to know if they are edible.

Botanist Bhakta Bahadur Raskoti agrees that climate change has affected the growth of edible grass for sheep and goats in high mountain areas. “Because of climate change, grass species from the Tarai are now found in the mountains, while mountain grasses have moved up,” he adds.

Shepherd Jore Pun, 43, used to have 350 sheep a few years ago, but now has only 250.

Jore Pun. Image by Rabin Pun Magar via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

Lukum used to be a large sheep-farming village in the Eastern Rukum district. Half of the 400 households here used to herd sheep and goats. Today, there are 500 households, but only 35 are pastoralists.

The Magar people make up the majority of the Rukum East population. To them, sheep rearing used to be a way of life here. The sheep are sacrificed during their festivals, and women make clothing from their wool. With the sheep gone, these traditions are now in decline.

“Our grasslands are depleting, and sheep rearing has become unfeasible,” says ward chair Mankaji Pun. “Moreover, young men are moving out for jobs in the cities or overseas. They are abandoning their ancestral occupation.”

Many men from here have left for the Gulf, Malaysia or India. Youth here are also increasingly finding routes to America. Only the women, the elderly and children are left.

Graphic via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

Almost every household here has at least one member migrated to the USA. These families spend as much as NPR. 6 million (USD 45,175) to make their way there, borrowed from local lenders at high interest.

Dilchan Pun Magar of Lugum was rearing sheep until three years ago. He had 200 of them. Unable to make a living, he also kept side jobs. He has now completely given up on sheep rearing and operates a hotel.

“We couldn’t modernise sheep farming. It was a lot of work, and we barely made any money, so I ended up leaving it altogether,” says Pun Magar.

Rassa Gurung is still supporting his family by selling sheep. He says he makes NPR 400,000 (USD 3,012) a year, and the income goes to pay for his children’s education. “But my children are not interested in taking after me. They think it is too much work,” he adds.

Image by Rabin Pun Magar via Nepali Times. Used with permission.

Jore Pun also cites the new generation’s lack of interest as a reason for the decline of sheep farming. He says, “People started going to school. Now, everyone is migrating. Sheep farming is a lot of work, after all.”

There are still about 22,000 sheep in Rukum East, according to the Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock Development. Two years ago, there were nearly 800,000 sheep across the country. It is now down to 770,000.

This decrease in sheep numbers has similarly affected the production of meat, down from 2,964 metric tons last year to 2,880 this year. Wool production has also decreased, from 584,000kg two years ago to 567,412 this year.