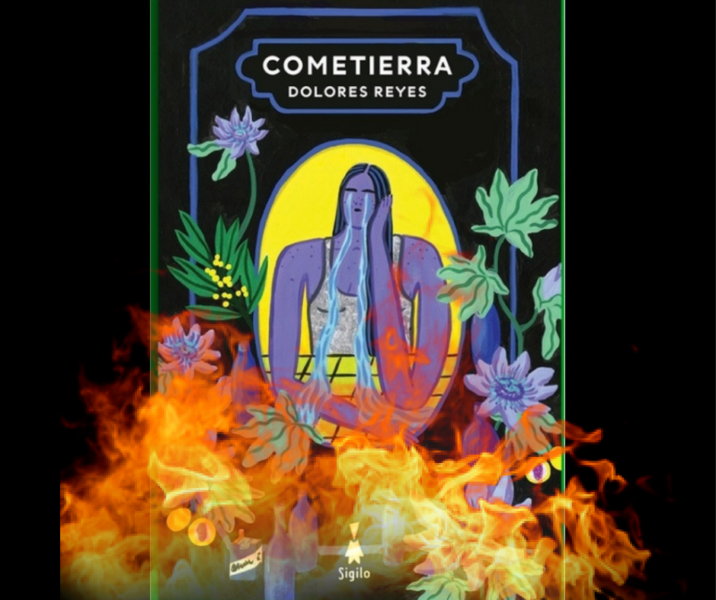

Collage with the cover of the novel “Cometierra,” by Dolores Reyes. Image created with Canva by Global Voices.

At the beginning of November, Argentine feminist literature became embroiled in a controversy. On her X (formerly Twitter) account, the Argentine vice president, Victoria Villarruel, denounced the actions of the Governor of Buenos Aires, Axel Kicillof, for allegedly distributing copies of the novel “Cometierra” (Earth-eater) in classrooms in the province, branding the content as “degrading and immoral,” and citing excerpts containing sexual scenes.

“Cometierra,” by Dolores Reyes, is one of the feminist works that the current Argentine government is seeking to censor, alleging “sexually explicit content” that is unsuitable for adolescents. The campaign aims to remove these books from school and public libraries, but up to now has not been successful.

A cry against gender-based violence and an ode to healthy relationships

Since its publication in 2019, “Cometierra” has sold more than 70,000 copies and has been translated into fifteen languages.

The novel focuses on femicides and tells the story of a young psychic from the outskirts of Buenos Aires (known as Greater Buenos Aires) named Cometierra. A special gift enables her to find missing people — usually women, girls, and boys — by eating a handful of dirt those people stepped on.

Unfortunately, most of the time these people have been violently killed. Cometierra, in turn, is also an orphan because of a femicide: her father beat her mother to death when she was a child.

Although the story is centred around extremely tragic situations, it also highlights the importance of emotional bonds, the protection of an older brother, close friendships that support and strengthen us, care and love.

In 2023, Dolores Reyes published her second novel, “Miseria,” a sequel that continues to follow the life of Cometierra, her brother and her sister-in-law, Miseria, in the city of Buenos Aires.

Why so scandalous?

In September of 2023, the government of Buenos Aires Province launched the program Identidades Bonaerenses (Buenos Aires Identities), that includes a catalog of more than 100 literary works of fiction and non-fiction that relate to the territory, the customs and cultural identity of the province. Thousands of copies were purchased to be distributed in secondary and adult schools, technical schools, teacher training institutes, public and popular libraries, and prison libraries. Among these works is “Cometierra.”

The catalog was wrongly associated with the Educación Sexual Integral (ESI) (Comprehensive Sexual Education) program, the content of which is compulsory at all levels. This is not the case, as the catalogue corresponds to a non-compulsory program to promote reading, and details the minimum age recommendations and teacher support for this and other works.

Taking advantage of the controversy, an association for the defence of the “well-being of children and adolescents” has filed a criminal complaint against the General Director of Culture and Education of the Province of Buenos Aires, Alberto Sileoni, for the “corruption of minors, dissemination of pornographic material to minors and abuse of authority.”

At the center of this scandal, Dolores Reyes says that she has received an infinite number of threats and attacks on social media. In response to the vice president's allegations about her novel, the author told media outlet Infobae:

Cometierra es una forma de narrar un pedido de justicia: una chica que falta, una historia que fue silenciada, y por lo tanto no escuchada. El silenciamiento es una de las armas más efectivas de la violencia de género.

“Cometierra” is a form by which to narrate a demand for justice: a missing girl, a story that was silenced, and therefore not heard. Silencing is one of the most effective weapons of gender-based violence.

A gloomy #25N for Argentina

November 25 was the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, a date that has been commemorated since 1999, by a United Nations resolution in honor of the Mirabal sisters who were brutally executed by the dictator, Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic on November 25 1960.

However, this is the first time that Argentina has experienced this day in the midst of a clear institutional retreat and denial regarding gender-based violence. This in a country where 168 femicides were recorded in the first half of 2024 alone, of which 31 involved prior complaints (17 with precautionary measures in force) and where at least 155 minors lost their mothers to femicide. Policies related to gender equality and support seem to be more of a hindrance than a priority.

Having just assumed office, Javier Milei's government, from the La Libertad Avanza (LLA) (Freedom Advances) party, began the dissolution of the Ministry of Women, Genders and Diversity, and reduced it to an undersecretary of Protection against Gender-based Violence, which was shut down permanently in less than three months. This de-funded support programs for women and sexual diversity, and left thousands of victims of gender-based violence unprotected.

Furthermore, in February of 2024, the government announced the closure of the National Institute against Discrimination, Xenophobia and Racism, alleging that it was “the ‘Cristinista’ thought police” (referring to Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, the former president and then vice president of Argentina). More than 400 people, who worked all over the country for the protection of minority rights, lost their jobs. The permanent closure was finalized in August 2024.

As if that were not enough, and in a context of inflation that worsens the situation, in August 2024, the LLA government introduced changes to the Acompañar program, which provides financial assistance to victims of gender-based violence, and reduced the economic allocation equivalent to the minimum living wage for workers from six to three months, which makes it more difficult to leave violent situations.

In addition to this set of actions that threaten the safety and support of victims of gender-based violence, there are several more that threaten the great achievements in terms of gender and equality. Among them, the elimination of the resolution that required gender parity in companies and civil associations, the modifications to the Micaela Law, which made gender training mandatory for members of the three branches of government and which is now required only for those who work “in bodies competent in the matter.”

The Registradas program, which promoted the formal incorporation of domestic workers into the labor market, was also ended; the use of inclusive language and everything related to the gender perspective in public administration was prohibited; the pension moratorium — of which the main beneficiaries were women, since they could retire without the required 30 years of contributions — was eliminated. It is usually women who have unregulated jobs or who leave the labor market to raise or care for families, so this measure directly targets them.

These are just some of the policies adopted by Argentina's government in its conservative and regressive “cultural battle” that is detrimental to the democratic agreement that has been in force for the last forty years.

What is also notable, is that the government seems to choose particular dates to apply these policies. For example, on March 8, International Women's Day, it changed the name of the Salón de las Mujeres Argentinas del Bicentenario (Hall of Argentine Women of the Bicentennial) in the Casa Rosada presidential palace to the Salón de los Próceres (Hall of Heroes), arguing that the previous name represented an inverse discrimination. The Hall of Women was a space created by the former president Cristina Fernández de Kirchner to honour the role and legacy of women in Argentina's history.

Read more: Women's rights are backsliding left and right in Latin America

On November 15, ten days before November 25, Argentina was the only country that voted against a United Nations resolution to eradicate violence against women. Almost simultaneously, this campaign to discredit feminist literature was unleashed, especially literature that addresses the problem of violence against women.

De vanguardia a verguenza: Argentina en el 25Nhttps://t.co/A84PCP42jj

— Luciana Peker (@lucianapeker) November 25, 2024

From progress to shame: Argentina on 25N

Finally, Milei's most recent announcement, on November 27, is just another element of his persecution against what he calls the “gender agenda”: he will eliminate by decree the non-binary ID card, established in 2021 after many years of struggle by LGBTQ+ organizations, and which made Argentina the first country in the region to recognize gender categories beyond the binary.

In addition to “Cometierra,” three other novels by feminist authors have been questioned: “Las primas” (The Cousins) by Aurora Venturini, “Si no fueras tan niña” (If you weren't such a girl) by Sol Fantin, and “Las aventuras de la China Iron” (The Adventures of China Iron) by Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, which were also included in the Identidades Bonaerenses catalogue.

Collective Resistance

Calls for collective readings of “Cometierra” have gained traction in different cultural and academic spaces as a direct response to the attempts at censorship promoted by sectors of the government. These events have brought together writers, readers and social organizations in libraries, theatres and other public spaces with the aim of making the work of Dolores Reyes visible and defending free access to literature.

One of the most notable gatherings took place at the Picadero Theatre in Buenos Aires, where more than one hundred writers participated in a public reading of the novel. These activities, in addition to supporting the author, have contributed to generating a debate about the importance of freedom of expression and the role of literature as a reflection of social problems.

View this post on Instagram

Books are the builders of community, of its multiple identities, of its stories, of its values, of its debates and discussions, of its disagreements and of its meeting points. The Argentine literary tradition is a true wonder for men and women alike and has a global projection of enormous importance and prestige. Books, and fiction in particular, are tools of knowledge that link people’s lives and are deeply intertwined with education. Libraries and classrooms have in teachers and librarians the ideal and trained mediators that allow reading to accompany educational development at all levels of public and private education so that it can illuminate and generate debates. It is in these places that citizens are formed. That is why it is imperative that Argentine literature: current literature, that of the country’s early days, that of the native peoples who preceded us, be available to students and readers throughout the country. In line with this, Argentine writers, and writers from various places in Latin America and Spain, call for an unrestricted defence of books, reading schemes and libraries. Writers are not hostages of any regime or any electoral campaign. We cannot allow neither the censorship campaigns nor the violent personal attacks on any writer, male or female, over disputes that have nothing to do with the objectives of our work. Readers, writers, both male and female: books, free from all current disputes and all censorship.

And this avalanche of support and protests is compounded by the almost inevitable result when an attempt is made to censor a work: record sales in recent weeks that have made “Cometierra” the best-selling work, even above South Korean Han Khan, winner of the 2024 Nobel Prize for Literature.

This is not the first time that an unintentional “publicity campaign” by the libertarian Argentine government has boosted the careers of women it attacks or seeks to discredit: at the end of September, the music video by singer-songwriter and actress Lali Espósito, where she mocked Milei’s attacks against her, became the most viewed video worldwide.